Key organisations mentioned:

Key terms:

- Sexual offences

- Consent

- Sexual harassment

- Protection orders

- Criminal justice

- Prosecution

- Victim impact statements

- Civil claims

- Restorative justice

Introduction

Victim-survivors may engage with the ACT justice system in several ways following an experience of sexual violence. They may be asked to participate in the criminal justice process if charges are brought against the perpetrator. They can also apply for a protection order to minimise the risk of immediate or future harm, pursue compensation through the civil law courts and/or seek mediation through the ACT’s restorative justice process. Victim-survivors are able to pursue more than one legal avenue in relation to an experience of sexual violence. The unique experiences of each victim-survivor in the ACT (and their personal preferences) will determine which legal avenues, if any, are appropriate.

It must be acknowledged that, as it currently exists, the legal system in the ACT carries a risk of causing further harm to victim-survivors. Legal processes have a reputation for creating an environment where victim-survivors feel they are subjected to victim-blaming, re-traumatisation and unfair treatment. These processes require significant investment of time and energy. This chapter provides a foundational overview of the legal avenues available to victim-survivors in the ACT and reflects how these systems are meant to operate. We acknowledge the lived experiences of the victim-survivors who have been unable to achieve justice and healing through the legal system due to stigma, systemic barriers and discrimination.

Important Definitions

Consent

Consent means the informed agreement to a sexual act that is freely and voluntarily given, and communicated through words or actions. Under ACT law, a person does not consent to sexual activity in circumstances including, but not limited to, where:

In general, they are younger than 16 years of age (this is the age of consent in the ACT)

They said or did something to communicate withdrawing their agreement to sexual activity before or during the act

They are unconscious, asleep, or incapable of agreeing because of intoxication (due to alcohol, a drug or any other substance)

They are physically helpless or have a mental incapacity that makes it hard to understand the nature of the sexual activity

They are being unlawfully detained by the perpetrator

The perpetrator has used violence to force them into sexual activity

The perpetrator has threatened to blackmail, publicly humiliate, harass or hurt them or someone else if they don’t agree to sexual activity

The perpetrator has intentionally lied to the person to make them engage in sexual activity (e.g. lying about their identity or about using a condom)

The perpetrator is in a position of authority, dependence or trust (e.g. a teacher, parent, employer or doctor) and has used this to make the person engage in sexual activity.

Silence or lack of resistance does not necessarily mean a person consents to sexual activity. Consenting to one sexual act does not mean there is consent to another act. Consenting to sexual activity with one person does not mean there is consent to sexual activity with another person.

Family, domestic and intimate partner violence

Family violence is an umbrella term used to describe a broad range of offences and conduct that causes fear for one’s safety and/or wellbeing or is otherwise abusive. Family violence occurs when a family member (which includes a current or former intimate/domestic partner, parent, step-parent or in-law):

Is physically violent or abusive

Is sexually violent or abusive

Is emotionally or psychologically abusive

Engages in economic abuse, and/or

Is threatening or coercive.

Family violence can also include damaging property, harming an animal, stalking, removing a person’s free choice or causing a child to be exposed to family violence. For more information about family violence, see the Resources page.

Intimate partner violence, also commonly referred to as ‘domestic violence’, refers to a pattern of behaviour by a current or former intimate partner that causes physical, sexual or psychological harm, including physical aggression, sexual coercion, psychological abuse and controlling behaviours.

Sexual Violence and the Law

Sexual assault is illegal in all Australian states and territories, regardless of the relationship between the people involved. This includes intimate partners and married couples. Sexual assault is criminalised under Part III of the Crimes Act 1900 (ACT), which makes it a crime for a person (or group of people) to use violence, threats or coercion to force someone to have sex.

The term ‘sexual assault’ is more commonly used to describe a wide range of sexual violence and harmful behaviours. In this section, some of the main sexual offences in the ACT are outlined. For more information about sexual violence outside of the law, see the Understanding Sexual Violence page.

Sexual Offences

Sexual assault

Under sections 51, 52 and 53 of the Crimes Act 1900 (ACT), a person commits sexual assault if they inflict harm on another person, or threaten to inflict harm, with the intent to engage in sexual intercourse with that person or another person nearby.

Sexual intercourse without consent (rape)

Sexual intercourse without consent is commonly referred to as 'rape'. This crime is committed when a person (either alone or with others) engages in sexual intercourse with another person without their consent.

Under section 50 of the Crimes Act 1900 (ACT), sexual intercourse is defined as penetration of the genitalia or anus by either a body part of another person or an object, the insertion of any part of the penis into another person’s mouth and/or the stimulation of a person’s genitalia with another person’s mouth.

Technology-facilitated abuse

Under section 474.17 of the Criminal Code Act 1995 (Cth), it is a crime to use a carriage service (any form of electronic communication, including emails, text messages, phone calls and social media messaging services) in a way that is menacing, harassing or offensive. This is commonly referred to as technology-facilitated abuse.

Examples of technology-facilitated abuse include (but are not limited to):

Sending any abusive messages through a carriage service, such as through social media, texts, emails or bank transfer descriptions

Making repeated controlling or threatening phone calls

Checking someone’s text messages, social media activity, internet activity or location history

Forbidding someone from having a phone or limiting who they can contact via phone or internet

Tricking someone into unknowingly downloading spyware that will allow a perpetrator to stalk, monitor and/or spy on them

Sharing intimate photos of someone without their consent (sometimes referred to as ‘intimate image abuse’ or ‘revenge porn’).

Intimate image abuse

Under section 72C of the Crimes Act 1900 (ACT), it is illegal for someone to distribute or threaten to distribute an intimate image of someone without their consent.

An intimate image is defined in section 72A as a photo or video that:

Shows a person’s genitalia, including if covered by underwear

Shows a woman-identifying person’s breasts, including if covered by underwear

Shows a person who is undressed, showering, bathing, using the toilet or engaged in sexual activity

Depicts a person in a sexual manner or context

Has been edited or altered to show any of these things.

Distribution includes sending or showing the image to someone else or making it available for another person to view or access, even if no one ends up actually viewing or accessing the image.

Note: Possession or distribution of intimate images where the person shown is under the age of 18 may be an offence under child abuse material laws.

Acts of indecency

Acts of indecency are criminalised under sections 57, 58, 59, 60 and 61 of the Crimes Act 1900 (ACT). They include behaviours that are ‘unbecoming or offensive’, or otherwise fall below the common standard of decency that an average person would expect. An act of indecency might include the below behaviours without consent or in an inappropriate context:

Exposing oneself in front of a child or in public

Sending an unsolicited sexually explicit photo of oneself to another person

Pretending to perform a sexual act on another person

Touching someone's genitals without penetration or touching someone's breasts.

Child sexual abuse

Child sexual abuse includes any act that exposes a child to, or involves a child in, sexual processes that are beyond their understanding, are contrary to accepted community standards, or are outside what is permitted by law.

Such acts include:

Fondling the genitals or breasts

Masturbation

Oral sex

Sexual intercourse

Voyeurism (watching a person who is engaged in a private act without their consent, for the purpose of becoming sexually aroused or gratified)

Exhibitionism (exposing the genitals or being observed engaging in sexual activity, also known as ‘flashing’)

Exposing a child to, or involving achild in, pornography

Child grooming (deliberately befriending or establishing an emotional connection with a child to lower that child’s inhibitions in preparation for sexual activity)

Producing, consuming, disseminating or exchanging child sexual abuse material (including intimate images of children).

Offences related to child sexual abuse include those listed in sections 55, 55A, 56, 61, 61A, 64, 64A, 65, 66, 66AA, 66AB, 66A, 66B and 72D of the Crimes Act 1900 (ACT). In the ACT, the age of consent is 16. However, there are some sexual offences that apply to conduct involving a person who is under 18.

Sexual harassment

Sexual harassment occurs when someone engages in unwelcome conduct of a sexual nature (including making sexual statements, requests, jokes or advances) which makes another person feel offended, humiliated or intimidated. This includes engaging in an act of indecency and/or unwelcome behaviour that can be considered ‘seriously demeaning’ because of a person’s gender identity. Sexual harassment can be a single event or a pattern of conduct and behaviour.

Sexual harassment can be unlawful under the Sex Discrimination Act 1984 (Cth) and the Anti-Discrimination Act 1991 (ACT). While it is not necessarily a criminal offence to sexually harass someone, a person who has experienced sexual harassment in certain contexts (including workplaces, educational institutions, clubs and employment services) can make a complaint or apply for compensation or disciplinary action against the perpetrator. It is illegal for someone to threaten, intimidate or attempt to persuade someone not to make a sexual harassment complaint or to withdraw one already made.

For more information about options available following sexual harassment in an institutional setting, see the Schools and Workplaces page.

Legal Avenues following Sexual Violence

Victim-survivors who have immediate concerns for their safety following an experience of sexual violence should contact ACT Police on Triple Zero (000) or a trusted person.

Protection Orders

If you are concerned for your safety following an incident of sexual violence, you may apply to the ACT Magistrates Court for a protection order against the perpetrator. This is an order of the court which sets conditions that the perpetrator must abide by.

These conditions may include prohibiting the perpetrator from:

Contacting or approaching you

Causing or threatening personal injury to you

Harassing, intimidating or behaving in an offensive manner towards you

Attending your home or workplace.

There are three types of protection orders: Family Violence Orders (FVO), which will generally apply for two years, Personal Protection Orders (PPO), which will generally apply for one year and Workplace Protection Orders (WPO), which can apply for a maximum period of one year. There is no cost to apply for these protection orders. For more information about applying for a WPO, see the Schools and Workplaces page.

An FVO can be issued if a person has been affected by or fears family violence. Family violence is defined in section 8 of the Family Violence Act 2016 (ACT) and includes sexual violence or abuse by a family member, current or former intimate partner, or relative. A person can apply for an FVO on behalf of children who live with them. A police officer may also apply on behalf of an individual. Police may also automatically issue a protection order against the perpetrator following an arrest. For more information about family violence, see the Useful Resources page.

A PPO can be issued if a person fears personal violence from someone who is not a family member or domestic/intimate partner. ‘Personal violence’ includes physical and sexual violence or abuse, threats, harassment, offensive or intimidating behaviour, stalking and property damage. A person can also apply for a PPO on behalf of children under the age of 18 who ordinarily live with them.

Under the National Domestic Violence Order Scheme, all PPOs and FVOs made in the ACT after 25 November 2017 are nationally recognised. This means that they can be enforced in all Australian states and territories and in New Zealand.

How to apply

To apply for a PPO or FVO, you must lodge an application at the ACT Magistrates Court. You can also contact the ACT Police to file an application on your behalf. The Court is located at 4 Knowles Place, Canberra ACT 2601. There are services available there to assist you with lodging an application, including:

ACT Policing Family Violence Liaison Officers, located in the Family Violence Unit at the ACT Magistrates Court

Legal Aid ACT lawyers

Domestic Violence Crisis Service (DVCS) staff.

You can also contact the Domestic Violence and Personal Protection Order Unit at Legal Aid ACT for legal assistance in drafting your application. This service is not means tested, meaning that anyone can seek initial advice for free. See the ACT Support Services page for contact details.

Complete the relevant application forms

To apply for a PPO or FVO you will be required to file the following documents:An application form outlining the conditions that you seek from the court to keep you safe from the other party and your explanation of the incident/s involving the other party

Private and Confidential form (the yellow form) which is provided to the police by the court to assist in locating the perpetrator, and

A Notice of Address for Service, which includes your contact details (or those of your lawyer) to receive communication from the court regarding your PPO or FVO.

The above forms are available at the Registry Counter inside the main foyer of the ACT Magistrates Court or on the ACT Courts website.

File the application

The above forms must be lodged in hard copy at the Registry Counter inside the ACT Magistrates Court. The Registry Counter opens at 9am. Waiting in the court for the opening time may be a confronting experience. If needed, bring a support person or access the support services available in the court. The court will hear your application within 48 hours of it being filed. You will be given a notice that lists the file number of your application, the time of your hearing and the details of the presiding officer (Deputy Registrar or Magistrate) who will hear your application.

Appear before the Deputy Registrar/Magistrate

At the hearing, you will be required to give oral evidence, explain the details of your application and why you are seeking a protection order. A support person can accompany you to this hearing.

Interim Decision

At the conclusion of the hearing, the court may make an Interim Family Violence Order (IFVO) or Interim Personal Protection Order (IPPO) if they are satisfied that the order is necessary to ensure your safety and the safety of your property until a final decision is made. Upon making the interim order, the court then makes arrangements for ACT Policing to serve the perpetrator with the interim order. The interim order does not become enforceable until all documents have been served. If the court does not make an interim order after hearing your application, a date will be set for a return conference.

Return Conference

After an application has been made, even if the court has not made an interim order, the court will set a date for a return conference. You and the perpetrator will be required to attend court for this return conference to see if the matter can be resolved through mediation. At the conference, the mediator will try to facilitate an agreement between you and the perpetrator about the terms of the order. You will not be required to sit in the same room as the perpetrator or communicate with them directly during this meeting. If there is an agreement on the terms of the order, the order will then be made final. If no agreement is reached, it will proceed to a Pre-Hearing Mention. A Pre-Hearing Mention is when the Registrar gives instructions on how to prepare for the hearing and to provide an additional opportunity for the order to be finalised with the consent of both parties. If no finalisation occurs at this point, then the matter will proceed to a final hearing.

Final Hearing

If no agreement is reached, the matter proceeds to a final hearing. In preparation for your hearing, you may file further court documents and evidence to support your application. On the date of hearing, you and the perpetrator will be given another opportunity to resolve your matter through mediation. If you do not reach an agreement, then your matter will be heard before the Deputy Registrar or Magistrate. After hearing each of your arguments and evidence, the Deputy Registrar or Magistrate may make a Final Family Violence Order or a Personal Protection Order against the perpetrator.

If there has been a breach of your protection order

If a person refuses or fails to comply with the terms outlined in the protection order, they are in breach of the order. This is a criminal offence. If this occurs, report it to the police as soon as you can. Call Triple Zero (000) if it is an emergency or life-threatening situation. If you can, keep a record of information such as the date, time, location and details of the breach, including any communication or attempted communication. Keep the order with you, as this will assist police when they respond to an incident.

More information about the process of obtaining a protection order is available on the ACT Police website, the ACT Magistrates Court website or can be obtained by calling the Legal Aid ACT helpline on 1300 654 314.

Sexual violence and your visa

If you are concerned for your safety following an incident of sexual violence, you may apply to the ACT Magistrates Court for a protection order against the perpetrator. This is an order of the court which sets conditions that the perpetrator must abide by.

If you are in Australia on a Temporary or Partner visa, your visa will not be automatically cancelled due to domestic, family or sexual violence. A perpetrator of domestic, family or sexual violence cannot cancel your visa. Only the Minister for Immigration or a delegated officer has this power. However, this is a complex policy area and outcomes can vary for different visa holders based on the type of visa.

If you have concerns or questions about your visa status because of domestic, family or sexual violence, it’s important to seek immigration assistance from a lawyer or registered migration agent. You can also contact the Department of Home Affairs via its website for assistance to resolve your visa status. The Department of Home Affairs will not refer the matter to the police without your consent unless there is immediate threat to your life, risk of harm or due to mandatory child reporting obligations.

The Australian Red Cross can also provide financial assistance to temporary visa holders who are experiencing domestic, family or sexual violence. For more information about your options or to seek support, you can contact Legal Aid ACT (see the ACT Support Services page for contact details), DVCS (see the ACT Support Services page for contact details) or visit the Family Violence Law Help website.

|

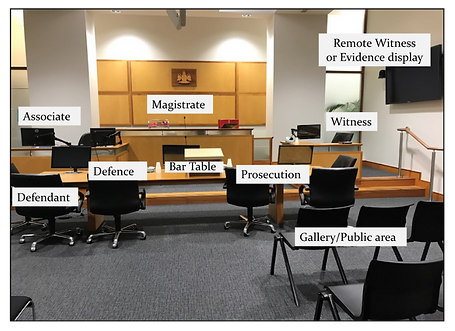

ACT Magistrates Court - Standard Court Room |

The Criminal Justice Process

If a sexual offence has occurred, you can report it to the police. This is the first step in bringing criminal charges against the perpetrator. Most sexual offences in the ACT are tried in the ACT Supreme Court. To learn more about making a report to police, see the Police and Investigation page.

When will a matter proceed to court?

Once police have investigated a sexual violence matter and have decided that there is a basis to lay charges, the matter is given to the ACT Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP), who will evaluate whether it should proceed to court.

Not all sexual violence matters proceed to court, even after a police investigation. Prosecutors must consider a range of factors in their evaluation, including:

Whether there is sufficient evidence

Whether there are reasonable prospects of the case being argued successfully and a conviction being obtained, and

Whether bringing the matter to court is in the public interest.

When is a matter in the ‘public interest’?

If a prosecutor is satisfied that there is sufficient evidence and a likelihood of conviction, they will then determine whether pursuing a conviction is in the public interest. Many factors are relevant in determining public interest and are assessed on a case-by-case basis. Examples of factors taken into account are:

The seriousness of the alleged offence

The youth, age, background, physical health, mental health or special vulnerability of the perpetrator, a witness or victim-survivor

The availability and effectiveness of alternatives to prosecution

The likely length and expense of a trial

The views of the victim-survivor.

This is a non-exhaustive list and many factors can be taken into account. While victim-survivors cannot decide whether a matter ultimately proceeds to court, their views are often given significant weight by the DPP (especially in sexual offence cases).

Victim-survivors whose matters proceed to court are often called to give evidence during the trial, which can be very distressing. This means that the DPP must also consider whether the victim-survivor will be able to cope with giving evidence and experiencing a potentially lengthy criminal trial. Prosecutors will also need to assess the reliability and credibility of the evidence - this is a question of whether the jury or judge would be satisfied that the offence occurred, based on the evidence, beyond a reasonable doubt. This is a very high standard of proof. However, if the perpetrator of the sexual offence pleads guilty, they may be sentenced without the matter proceeding to a trial.

It may take years for a trial to begin in court after the incident was first reported to police. There is no standard length of time from initial police report to the beginning of court proceedings. There will likely be frequent delays which also lengthen the criminal justice process. However, if the victim-survivor is deemed to be a 'vulnerable adult', they may be able to give evidence at a pre-trial hearing so their involvement in the trial process can be finalised earlier. Due to this lengthy process, there is potential for re-traumatisation and further harm to occur. The criminal justice process may not be the right avenue for many individuals. It is important for victim-survivors to seek legal advice and professional support for more information about the criminal justice process.

|

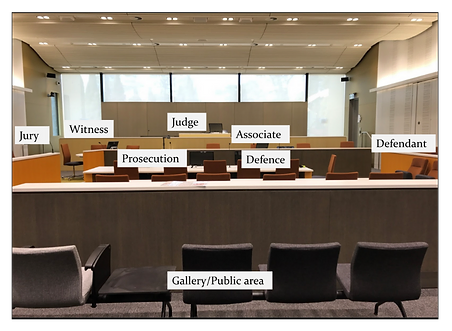

ACT Supreme Court - Jury Court Room |

Important organisations and services to know

ACT Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP)

The DPP are the lawyers responsible for prosecuting criminal offences in court on behalf of the ACT community. This means that, in sexual violence matters, the DPP are responsible for deciding whether a matter will proceed to court and then proving that the sexual offence occurred beyond a reasonable doubt.

Victim-survivors whose matters proceed to court will often be called as witnesses by the DPP to give evidence against the perpetrator. The DPP takes the victim-survivor’s interests and wishes into account throughout the prosecution. However, while the DPP may seek to prove that a sexual offence was committed, they do not represent victim-survivors in court.

Witness Assistance Service (WAS)

The Witness Assistance Service (WAS) is part of the DPP and is staffed by witness liaison officers. WAS gives priority to vulnerable witnesses, such as victim-survivors of sexual offences, people under the age of 18 or witnesses with a disability or mental health concerns.

WAS can assist victim-survivors whose matters proceed to court by:

Organising and attending meetings between victim-survivors and DPP lawyers in preparation for trial

Providing updates on the matter as it proceeds in court

Providing information to victim-survivors about their rights, any special provisions for giving evidence and available support services

Arranging court visits so that witnesses can familiarise themselves with the court environment

Assisting witnesses to prepare Victim Impact Statements

Providing information about verdicts and sentencing at the end of the trial.

Although WAS works with victims of crime, it does not work for them. WAS does not provide counselling, representation or seek to influence prosecutorial decisions or legal outcomes in any way.

Victim Support ACT

Victim Support ACT provides support, advocacy and financial assistance to people who have experienced a crime in the ACT. Victim Support ACT also provides a Court Support Program run by volunteers who can provide practical information and assistance to victim-survivors attending the ACT Magistrates Court and the ACT Supreme Court. For more information about Victim Support ACT, visit its website.

Intermediaries

Intermediaries are trained officers of the court who can be appointed in matters involving vulnerable witnesses for sexual violence cases. Vulnerable witnesses include children and can also include adults with a communication difficulty related to disability, trauma or cultural and linguistic background.

Intermediaries are often health professionals and are impartial, meaning that they do not represent the witness and cannot discuss the matter or content of the case. They do not act as a support person for the victim-survivor, but rather ensure that they are able to communicate effectively and safely with police, legal practitioners and other court staff during proceedings. Intermediaries can also be present during police interviews. For more information about intermediaries, see the Police and Investigation page.

If deemed necessary, the DPP may apply for an intermediary for a victim-survivor to facilitate communication during questioning at court. Victim-survivors who would like assistance from an intermediary can ask police when making a report or contact Victim Support ACT. The Court may also appoint a witness intermediary if necessary.

Note: The DVCS Court Advocacy Program can also support victim-survivors during criminal proceedings for sexual violence matters within a domestic and/or family violence context.

Before court

Prior to the trial, victim-survivors will meet with the DPP prosecutor/s who will be conducting the matter in court. A WAS liaison officer may also be present to support victim-survivors and assist with these preparations. Victim-survivors may be accompanied by a support person during the meeting.

During the court process

Most sexual offence proceedings in the ACT occur in the ACT Supreme Court, located at 6 Knowles Place, Canberra ACT 2601.

The proceedings in the ACT Supreme Court are heard in front of a 12-person jury who are responsible for deciding whether the accused perpetrator (often referred to as the defendant or the accused) is guilty or not guilty beyond reasonable doubt. A Judge is also present to guide the proceedings and sentence the perpetrator if found guilty. Other important people involved in sexual offence proceedings are the DPP prosecution team, the defence team (if the perpetrator has sought legal representation) and witnesses who may be called to give evidence, which usually includes the victim-survivor and investigating officers.

Before calling witnesses to give evidence, both the prosecution and defence teams will be given an opportunity to outline their case to the jury. This includes explaining the incident and the nature of the charges brought against the perpetrator.

Please note that the identity of victim-survivors involved in court proceedings must be kept confidential from the public and cannot be reported on by the media without the victim-survivor's consent. While this same confidentiality is not given to the perpetrator, their name will be withheld if it reveals the victim-survivor's identity. However, a victim-survivor may choose to have their identity reported on.

The courtroom and remote witness facilities

In sexual violence or domestic violence matters, victim-survivors sit in a separate room near the courtroom (a ‘remote witness facility’) to give evidence. This is to protect them from seeing the perpetrator directly in the courtroom. Both the remote witness facility and courtroom are linked via videolink, so that everyone in the courtroom can see and hear the victim-survivor give their evidence. A support person, such as a friend or family member, or a support animal, can sit with the victim-survivor in the remote witness facility as long as they are not giving evidence too. Staff from the CRCC or the DVCS can also support victim-survivors while giving evidence. Victim-survivors may also ask to give their evidence in the courtroom if they wish. This decision is a personal choice of the victim-survivor about where they feel best to give their evidence.

|

Remote Witness Facility |

Giving evidence: Examination-in-chief and cross-examination

Victim-survivors will be required to give evidence during the trial by answering questions about their witness statement.

First, the DPP prosecutor will ask questions about the sexual violence incident and the information contained in the witness statement. If there was a recorded statement made to police, this will be played to the court and the prosecutor may ask follow up questions (to learn more about recorded statements, see the Police and Investigation page). This is called examination-in-chief. The purpose of these questions is to allow the jury, judge or magistrate to understand the victim-survivor’s full account of the facts.

Next, the defence team will ask the witness questions about their answers. This is called cross-examination. The purpose of these questions is to test evidence. For this reason, cross-examination can be incredibly distressing or re-traumatising for victim-survivors. If the perpetrator is unrepresented, the court will appoint a registrar to cross-examine the witness on their behalf. There are certain topics that a victim-survivor cannot be cross-examined about, including their sexual history and confidential medical information (including counselling records), without the court's approval.

Victim-survivors can ask for breaks during examination-in-chief and cross-examination if necessary.

Child witnesses

For child witnesses in sexual offences, their evidence can also be presented to the court in the form of a recorded interview between the child and the police. A child will still have to attend court (using the audio-visual link) for any further examination-in-chief and cross-examination.

The verdict

The verdict is the jury’s decision about whether the perpetrator is found to be guilty or not guilty beyond reasonable doubt. If the perpetrator is found guilty in either the ACT Supreme Court or the ACT Magistrates Court the matter will proceed to sentencing. Sometimes the perpetrator is sentenced immediately, but usually a date is set for a future court hearing so that the judge or magistrate can consider the appropriate sentence. If the perpetrator has pleaded guilty, the matter will generally proceed to sentencing.

If the perpetrator is found not guilty, it does not necessarily mean that the jury, judge or magistrate did not believe the victim-survivor and/or the witness. It means that the charge against them could not be proved beyond a reasonable doubt or an additional factor influenced the verdict (for example, if the perpetrator is found to suffer from a mental impairment). The DPP might choose to appeal this decision.

After court

Sentencing

If a sentencing hearing has been set after a verdict has been reached, the offender will be required to return to court. Victim-survivors can attend the sentencing hearing but are not required to do so. Each sexual offence in the ACT carries a maximum penalty, but the judge or magistrate will decide the appropriate sentence in each matter. This may be a term of imprisonment, community service, mandatory counselling or some other form of obligation. The WAS and Victim Support ACT are available to explain verdicts and sentencing to victim-survivors during and after trial.

Victim Impact Statements (VIS)

Victim-survivors have the right to make a Victim Impact Statement (VIS) to the court at the time of sentencing. This is a written or spoken statement which describes to the court the impact of the crime and harm it has caused. This can include physical, psychological and emotional harm, economic loss and/or other damages.

VIS are voluntary. They can be read aloud in court during the sentencing hearing by the victim-survivor themselves, a support person, the prosecutor or be tendered to be read by the judge or magistrate at sentencing. The court may grant more time for a VIS to be prepared in a sentencing proceeding for serious offences (offences punishable by imprisonment for longer than five years). VIS help the court understand the personal impact of the crime on the victim-survivor and their supporters. A victim-survivor may be cross-examined by defence lawyers about their VIS. As such, a VIS can only refer to crimes for which the perpetrator was found guilty.

More information about VIS, including the Victim Impact Statement form for witnesses to fill out, can be found on the Victim Support ACT website. Victim Support ACT, DVCS, the WAS and VLOs can also assist witnesses in preparing their statements.

ACT Victims Register

If the perpetrator has been convicted and sentenced, victim-survivors can elect to have their name and contact details recorded on the ACT Victims Register to receive information about the perpetrator and the administration of their sentence. There are three registers in the ACT:

The Victims of Adult Offenders Register (generally referred to as the ACT Victims Register)

The Victims of Young Offenders Register (for perpetrators who were under the age of 18 when the offence was committed), and

The Affected Persons Register (used when the defendant or offender has been found not guilty by way of mental impairment).

For adult perpetrators, the information that a victim can receive once registered includes:

The length of their sentence, the date they will be eligible for parole and their earliest release date

The correctional centre where they are detained and any subsequent transfers between facilities

Any changes in their security classification which may result in the perpetrator being eligible for unescorted leave

Any unescorted leave given to the perpetrator, and

The death, escape or any other exceptional event relating to the perpetrator.

Information that is kept on the ACT Victims Registers is confidential and is only used to contact and inform a registered victim about a sentenced offender. Victim-survivors can contact Victim Support ACT for more information.

The Civil Process

Victim-survivors may also be able to bring a civil claim against the perpetrator following sexual violence. Unlike the criminal justice process, in which the perpetrator is either found guilty or not guilty of a criminal offence, the civil law process allows victim-survivors the possibility of compensation (usually monetary compensation, called ‘damages’) for the harm they suffered (or are still suffering) as a result.

In a civil case, it must be proved on the balance of probabilities that the incident occurred and that the perpetrator is responsible for the harm caused. This is a lower standard of proof than is required in a criminal trial. It means that the judge or tribunal must agree that it is more likely than not that the incident occurred and the victim-survivor suffered harm as a result. The judge or tribunal can then award damages to the victim-survivor based on the harm suffered (including emotional, financial and ongoing harm). All civil cases with claims up to $25,000 are heard in the ACT Magistrates Court.

Considerations when bringing a civil claim

Advantages

The legal standard of proof in civil law (the balance of probabilities) is lower than in criminal law, meaning that it may be easier for a victim-survivor to bring a successful claim.

Unlike in criminal proceedings for sexual offences where victim-survivors are most often called as witnesses only, civil proceedings allow victim-survivors (or their legal representative/s) to argue their case directly before the court.

Victim-survivors can receive financial compensation for the harm suffered as a result of the incident.

A civil claim can be brought against companies and businesses, not just individuals. This may be beneficial for victim-survivors seeking compensation for harm suffered in institutional contexts.

Evidence is given through a written statement prior to the case, so the witness is not required to give evidence on the spot or without the aid of this written statement.

Disadvantages

Bringing a civil claim can be very expensive. If a victim-survivor wishes to be represented by a lawyer, they must be prepared to pay legal and court fees for the duration of the case, and potentially more in the event that they lose (for example, in the form of costs to the defendant, if ordered).

Just like criminal matters, civil trials can be lengthy.

There is a similar risk of re-traumatisation for the victim-survivor in being asked to prove that the incident occurred and due to the length of the trial.

Risk of retaliation in the form of a counter-claim by the defendant. For example, a defamation claim being made against the victim-survivor for ‘false allegations’.

How to bring a civil claim

It is important to obtain legal advice before lodging a civil claim against a perpetrator. The ACT Law Society may be able to recommend private law firms to victim-survivors based on considerations such as income and location.

Legal Aid ACT may also be able to support some victim-survivors in bringing civil claims through a grant of legal aid, if there are reasonable prospects of success and the victim-survivor is unable to afford legal representation.

Restorative Justice

Restorative justice is another option open to victim-survivors of sexual violence. The ACT Restorative Justice Unit (RJU) is an ACT Government agency which facilitates restorative justice in the ACT community by involving victim-survivors, their supporters and the perpetrator in the process. The restorative justice process aims to provide:

Victim-survivors with an opportunity to talk about how the offence has affected them and others close to them

Perpetrators with an opportunity to accept responsibility for their actions

Victim-survivors, offenders and supporters an opportunity to discuss the harm that has occurred and what needs to be done to repair that harm, and

Perpetrators with an opportunity to repair the harm done by the offence.

Restorative justice focuses on healing from the impacts of crime rather than criminal prosecution or civil damages. The RJU is located at the Second Floor, Customs House, 5 Constitution Ave, Canberra ACT 2601. The RJU can be contacted on (02) 6207 3992 or by emailing restorativejustice@act.gov.au.

When can matters be referred to the RJU?

The RJU receives referrals from within the criminal justice system, meaning that the matter must have been reported to police, be before the court, or the offender must be serving a sentence or subject to an order. Victim-survivors can seek a referral at different points in the justice process and are encouraged to contact the RJU to find out more and to seek assistance to access a referral. Only sexual offences defined as 'less serious' under the Crimes (Restorative Justice) Act 2004 (ACT) are eligible for referral to the RJU before the matter goes to Court. Other sexual violence offences can be referred to the RJU alongside court proceedings or after sentencing has occurred. Restorative justice is voluntary, meaning that all people involved, including the perpetrator, must agree to take part.

The restorative justice process

The restorative justice process is focused on the needs and interests of each individual victim-survivor. This means that the process can look quite different from one case to another.

After receiving a referral, RJU convenors meet with the participants over a number of weeks to determine whether restorative justice is appropriate. The restorative justice process will only continue if it is safe to do so, and is likely to meet the needs of the victim-survivor. The perpetrator must show a willingness to accept responsibility for having caused harm and have the capacity to actively make amends.

If restorative justice is deemed appropriate, and all parties agree to take part, RJU convenors will facilitate a meeting to discuss the following:

What happened? The perpetrator will be asked to talk about what led up to the offence, as well as what happened during and after the offence took place. They will also be asked to reflect on how they think the victim-survivor and others may have been affected.

How were people affected? Starting with the victim-survivor, the convenor will ask everyone to share their thoughts about the offence, how they felt when the offence occurred and how they feel now.

How to make things better? Everyone will be asked to share their thoughts on how the impacts of the crime can be alleviated. For example, this may be in the form of an apology, financial reparations or any other agreement between the victim-survivor and the perpetrator about what the perpetrator needs to do in order to repair the harm caused by the offence.

Often, these meetings are held face-to-face with everyone in the same room. However, it is possible for participants to communicate indirectly if this is more appropriate. Victim-survivors may also choose to have another person attend restorative justice meetings on their behalf.

The RJU will work closely with victim-survivors to ensure they feel in control, are able to set boundaries around what is discussed and determine the timing and format of any communication. For example, it may not be necessary to talk about what happened if this may re-traumatise the victim-survivor.

The process can also be adapted for participants from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds to ensure that it is culturally appropriate and effective. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander victim-survivors can be supported throughout the entire restorative justice process by an Indigenous Guidance Partner, who can attend all preliminary meetings, the conference and support the victim-survivor in the post-conference period. For more information about the restorative justice process and the Indigenous Guidance Partner, visit the ACT Government - Restorative Justice website.

Important things to know:

Participants can withdraw their participation in the restorative justice process at any time.

Accepting responsibility during the restorative justice process does not prevent the perpetrator from pleading ‘not guilty’ if the matter proceeds to court.

Agreements reached during the restorative justice process must be fair and able to be carried out by the perpetrator, must not be unlawful or require the detention of the perpetrator, and must not be for a term longer than 6 months.

Agreements reached during the restorative justice process may be taken into account during sentencing if the perpetrator is found guilty of the offence in court. However, the court cannot take into account whether the perpetrator refused to participate or withdrew from the restorative justice process.